- Although Portia feels it necessary to point out that the lottery is fair, the usage of "fair" would signal otherwise. It is evident, in her tone and even words that she is not particularly fond of Morocco's skin color but hides it behind her hatred for her father's lottery. This is a result of cultural clashes between the white Christians and the Islamic Moors as the two religions and two races were always at odds due to differences in both beliefs and skin color. The usage of "fair" hints that even though technically Morocco has an equal chance with blind luck, the game, as seen later by Portia's sly skewing of the game, that it favors white Christians (Bassanio) in this predominantly white Christian Venice. This leaves Morocco once again being ousted in this foreign culture due to the clashing of his own culture.

- Turkish Shah

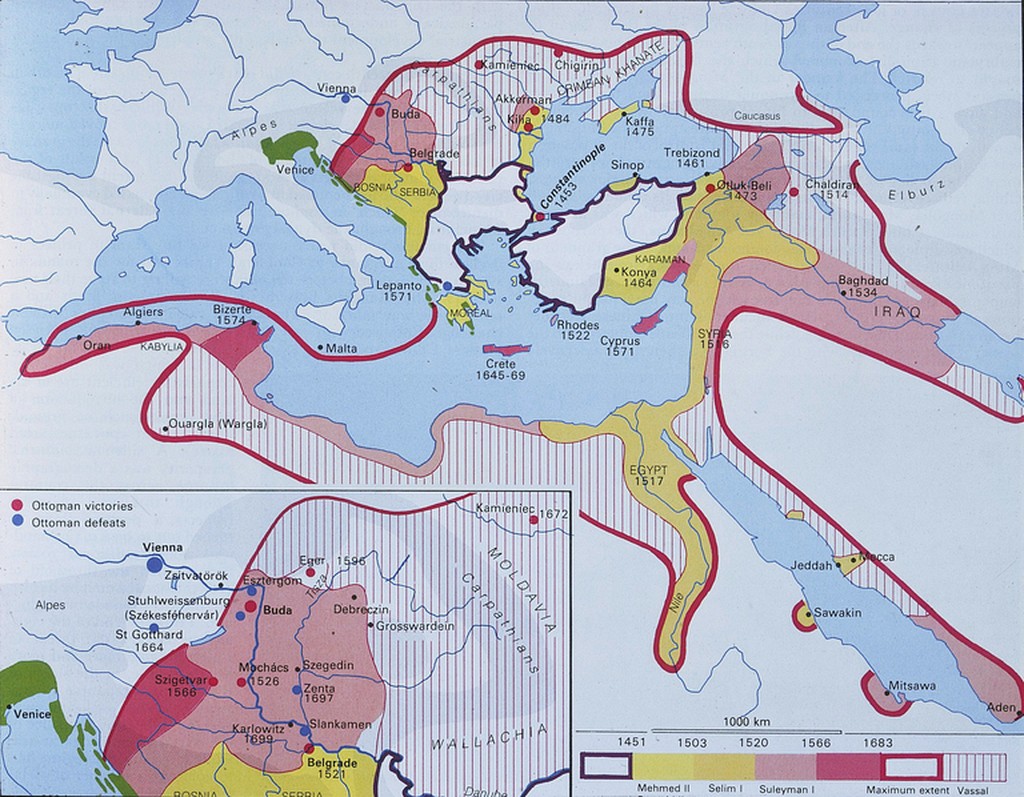

- In the 16th century the Ottoman Empire neighbored Morocco, as it extended all the way to Egypt and most of the African coasts bordering the Mediterranean Sea (see map below). This demonstrates a bit of the Moroccan culture being influenced by the Ottoman Empire as Morocco, Prince of Morocco, references a Central Asian sword (the scimitar), the Sophy and Persian Prince (Shah and Prince of Persia) and Sultan Solyman (a Turkish ruler) are all referenced by Morocco, who is from North Africa.

- The Ottoman Empire stretched out and occupied much of North Africa; however, they never occupied Morocco. Morocco references the tale of his scimitar sleighing powerful men from Persia and Turkey (parts of the Ottoman Empire), to show that he now wields the same power the sword had won from some of the most powerful rulers of one of the most powerful empires at the time (c.16th century.). In this he is attempting to compensate with proof of his bravery/strength to a Christian Portia for his undesired race. Nonetheless, these valiant tales are obsolete in a culture in which these traits are not valued as highly. There is a clash in the luck culture of Christians and the conqueror culture of Morocco

- Morocco is alluding to Hercules (the inhumanely strong Roman demigod turned god) and Lychas (Hercules' servant). In this metaphor, Morocco is projecting himself as Hercules, Portia's other suitors as Lychas, and the lottery as a game of dice. He, like Hercules, views himself as incredibly brave and strong, which he hopes compensates for his undesired race. However, even the strongest of gods can fall prey to luck, and in this case, Morocco is subject to the blind luck of the lottery. In this, he reveals his weakness, possibly hoping to win sympathy from a prejudice Portia as he knows Portia's white Christianity clashes with his Islamic background. He uses ancient Roman mythology to connect to Portia on neutral grounds, yet is still slightly connected to the now Christian Rome's past.

- Due to Morocco's extended metaphor, one can further connect the game of dice to the differences between Christian and Morocco's and even extended to Shylock's Judaism. Christianity is established to have gambling deep rooted in its culture. Most Christian characters believe in betting everything to luck in hopes of gaining more. In contrast, other cultures seem to struggle with this aspect. Shylock has previously expressed is unwillingness to loan to Antonio, knowing the odds of the loan not being paid off would be uncertain. Here, Morocco demonstrates his own qualms about blind luck through his Roman metaphor. His diction leans towards viewing blind luck as a weakness to even the strongest, which foreshadows his own "downfall" within this game of chance.

- Alternative name for Hercules (Greek Heracles)