- Lorenzo’s reference to his “constant soul” in the context of discussing Jessica’s qualities lends a religious dimension both to him and to Jessica. His “soul” has religious connotations, as the element of traditional Christianity that endures on into the afterlife, and the characterization of it as “constant” also plays upon this religious connotation. That Jessica is “placed” there imbues the relationship between her and Lorenzo with a religious element as well. Lorenzo exercises judgment in attributing certain qualities to her, and those judgements quickly create religious undertones considering that Jessica is a convert from Judaism to Christianty. By relating those qualities that make her worthy to share in Lorenzo’s “constant soul,” Shakespeare might be implying that these are specifically Christian qualities or, at least, that they are qualities which Christian characters value. Moreover, the fact that these judgements lead to her being “placed” within Lorenzo’s soul imply again religious connotation, as it echoes the same process of one being judged by the divine to be given a place in heaven.

- Referring to those taking part in the Bassanio’s masquerade.

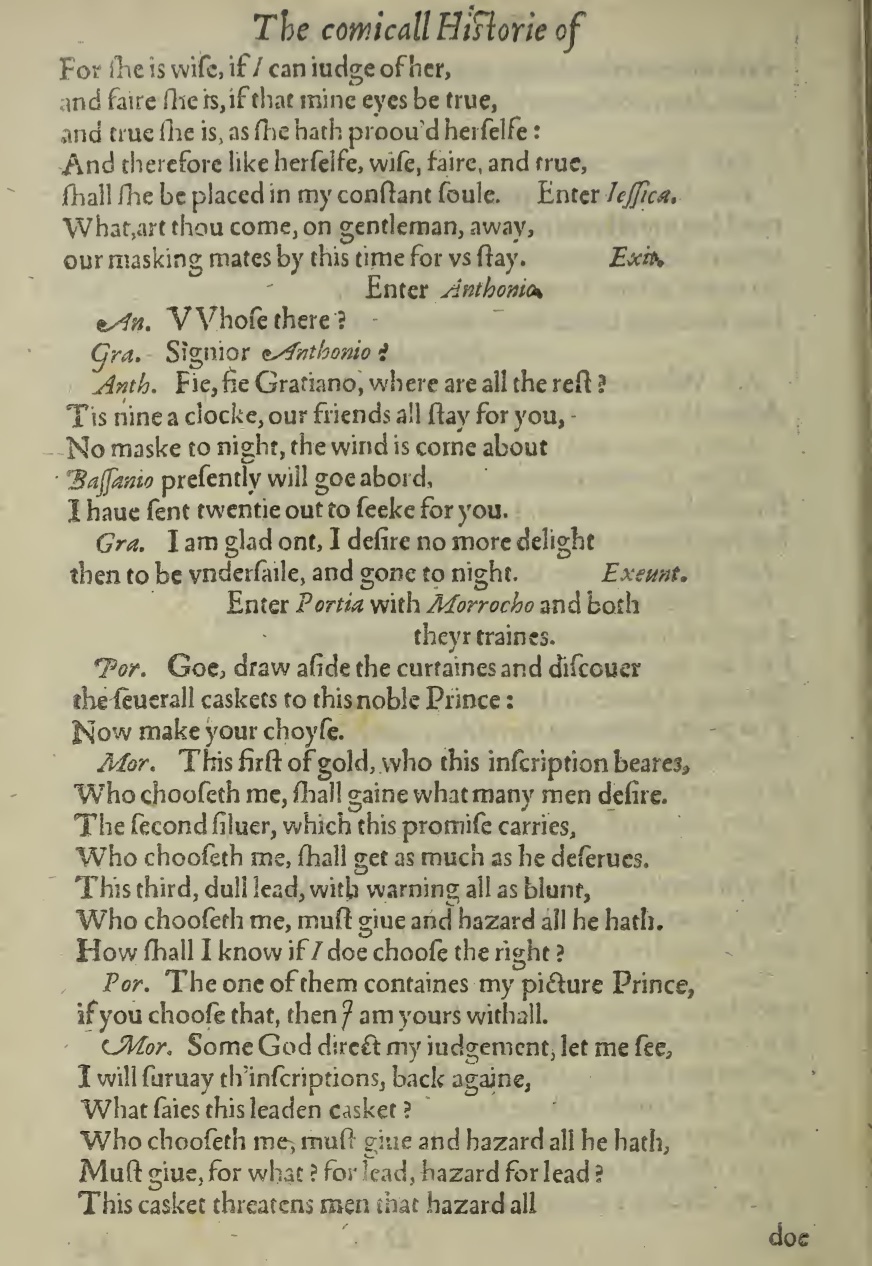

- Immediately. Shakespeare, William. “The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice.” The Norton Shakespeare: The Essential Plays/The Sonnets. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et.al. 3rd ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2015, pp. 300.

- Reveal or find. Shakespeare, William. “The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice.” The Norton Shakespeare: The Essential Plays/The Sonnets. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et.al. 3rd ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2015, pp. 300.

- Which. Shakespeare, William. “The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice.” The Norton Shakespeare: The Essential Plays/The Sonnets. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et.al. 3rd ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2015, pp. 300.

- Portia’s lead casket subtly points to religious themes of judgement. Since choosing this casket means to “hazard all he hath,” it plays into Christian ideas of faith. On one level, judgement is involved just in the deciding on whether or not to pick the lead casket; on another level, the choosing of one casket is, itself, a judgement of the character of the chooser. In other words, Shakespeare implies that to choose to hazard all speaks to a strong, positive character. In turn, this could be connected from a religious standpoint as a kind of “leap of faith, echoing Christian values of faith. Thus, this implies that to “hazard,” reflects both strong judgement (the correct course of action) and strong character (the correct kind of suitor).

- With it. Shakespeare, William. “The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice.” The Norton Shakespeare: The Essential Plays/The Sonnets. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et.al. 3rd ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2015, pp. 301.

- Morocco is asking for divine guidance as he evaluates the caskets. Daring to choose a casket in the first place is an incredible risk, and as he does not trust his own judgement, he wishes to pass it off to a higher power. The idea of great risk for great reward and relying on divine guidance is primarily associated with the business practices of the Christian characters, such as Antonio, who dare to send their wealth away on merchant ships in the hope of gaining more once they return. As such, it’s interesting that Morocco invokes this strategy by referring to “some God,” not the singular Abramahic God.