- Solanio comments on Antonio’s devotion for Bassanio, which is so immense that Antonio's biggest reason for living on this Earth is Bassanio. This devotion, which can be viewed as romantic love, shows what Antonio is willing to do for Bassanio. When viewed through a queer lens, Antonio willingly helps Bassanio woo Portia, perhaps knowing that a queer relationship would be looked down upon and that Bassanio does not view him in that way. Because of the bigoted society they live in (seen through the antisemitism Shylock faces and patriarchal society the women constantly have to navigate through), one can understand why Antonio would help Bassanio woo Portia since he knows he has no ability to safely have that relationship with Bassanio.

- Antonio's emotional health is discussed throughout the play and is actually the situation the characters are discussing in the opening of the play. In that opening scene, Antonio tries to figure out why he is depressed, and his friends ask him if it is associated with the safety of his ships, or perhaps love. Antonio denies both reasons, especially the latter, but although he logically explains that his ships are okay, he doesn't really give an solid explanation as to why his depression cannot be linked to issues with love. Antonio's 'heaviness' follows him throughout the play, but in this scene, Solanio and Salerio are discussing it because they are off to break the news to Antonio that one of his ships might be shipwrecked, which he had been so sure was safe in the opening scene. Solanio and Salerio think on how kind Antonio is, instantly coming up with examples of his generosity to in regards to Bassanio.

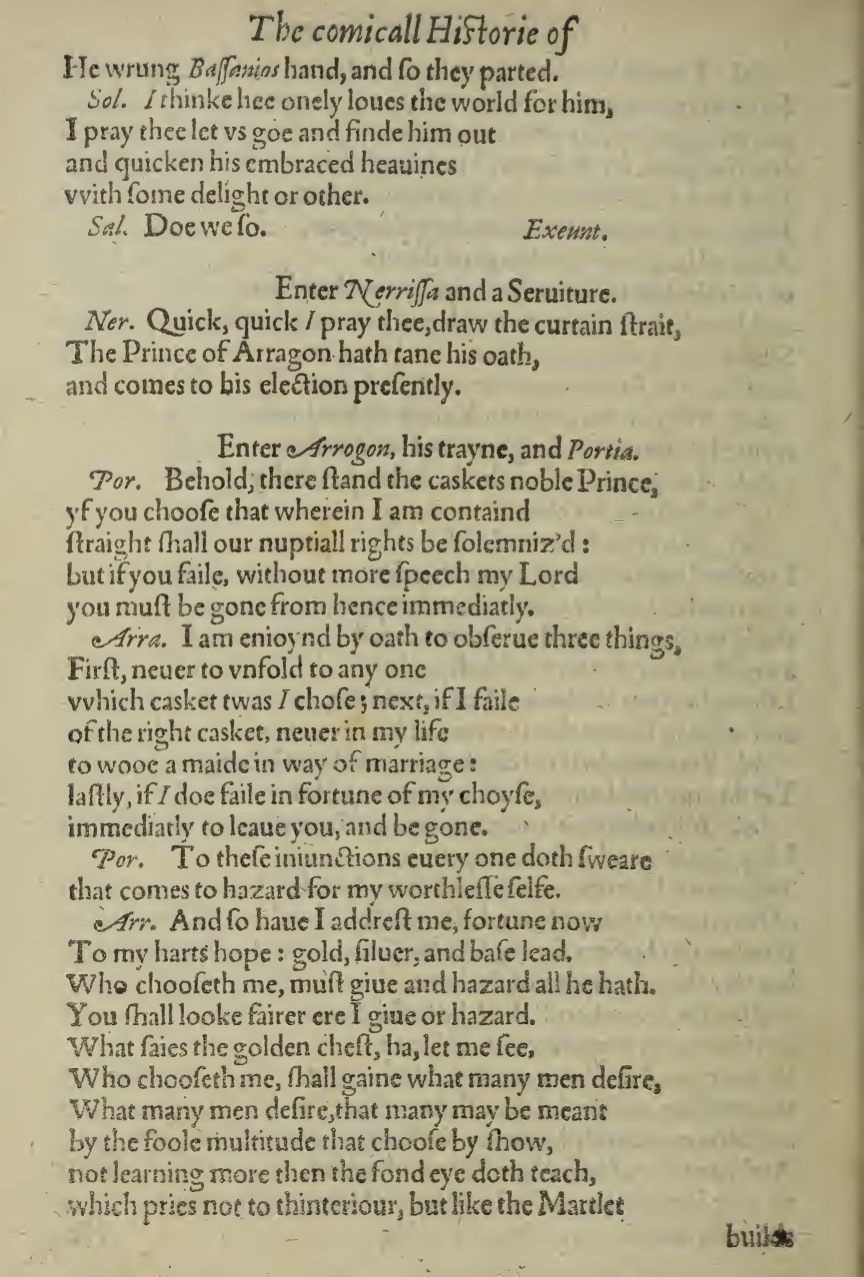

- The ability to marry Portia is found within a certain casket. This description objectifies her, containing her within a movable object. The women are also depicted as movable objects throughout the play as they move between men and their agency to love and build relationships with others is dependent on whether the men in their life (fathers and love interests) allow them to. A casket is also an interesting specification as Shakespeare could have used a word like box, package, chest, etc. but labeling the container as a casket additionally associates Portia and the marriage to the winning suitor with death, especially since her portrait is located inside the casket. Despite her father being dead, he continues to watch over her through this riddle, emphasizing his power as a dead man over Portia, a living woman. The portrait inside the casket further labels her as a object or prize to be won, and takes away her humanity.

- The rules of attaining Portia in marriage are listed, further stressing her inability of choice in her own marriage. Arragon holds the power here as the one to choose, putting the agency on him. It also stresses how serious the consequences of the riddle are, which only intensifies how precious Portia must be as a potential bride if the suitors are willingly attempting the riddle.

- If Arragon fails to get the riddle correct, one of the consequences is that he is unable to marry another woman. This would make it impossible to produce an heir and continue on with his family name, which is incredibly important as he is a prince. This would emasculate Arragon especially in such a patriarchal society, which is already emphasized in this scene since the riddle was created by Portia's dead father. By failing, Arragon loses his agency in relationships as well. However, where Portia as a woman and Antonio as a queer man lacks agency from birth due to gender and sexuality, Arragon willingly attempts this riddle, and his agency is lost only due to his own choice.

- Portia is smart in her word choice here, acknowledging her lack of agency in this situation and that she is worthless as she has no say in what is happening. Worthless contrasts with the idea of being kept in a coffin, a very valuable object. It also hints at her being kept in the lead coffin, the least valuable of the three options. Despite her not knowing the location of her portrait, she has a better idea than Arragon does of where she lies.

- The word ‘hope’ reflects the chance of the game. The wishes of her father cause Portia’s marriage to never be a result of choice, always chance. Portia is further seen as a movable object between men, as it is her father’s work that puts her fate in the hands of chance. While it is partially chance, the rest of the riddle needs to be parsed through. Arragon is given the opportunity to interpret the riddle and make a decision, his ‘hope’, is based on his wit, and his decision. Regardless of what Portia may be able to devise of the riddle, she is left without choice while Arragon has the ‘hope’ that the fortunes are in his favor.

- As Arragon looks at the caskets, he discusses the metal that they are all made of, connecting to the play's theme of money and greed. Not only is Portia's hand in marriage connected to death through the caskets, the metal of the caskets also connects to her worth, which objectifies her once again. Portia's portrait is actually found in the lead casket and not in the silver or gold, which means that the suitors must look beyond simple desire and greed.