- The choice to use the word bosom speaks to an interesting moment of gender identification in regard to commodification. The term bosom did not originate as a way to describe a woman’s breasts, but rather to describe a place of intimacy and enclosure. As a result, bosom over time has taken on the meaning of chest, breast, variations of a safe space, and, intriguingly in the context of this play, a ship’s cargo hold. In The Merchant of Venice, Antonio’s three ships were disastrously lost at sea, furthering his sense of debt to Shylock. Thus, when Portia demands Antonio lay his “bosom bare”, she is indirectly referencing his empty cargo holds. This conflation between the physical body (bosom as chest) and material goods (bosom as a ship’s cargo hold) underscores one of the major themes of the play in which the commodification of the body reduces the body to yet another means of exchange. The notion of the body as a good to be consumed is particularly present not only in this scene, but in the overall use of marriage in the play, where women are married to men who, in effect, are paid for the marriage and gain access to their wives’ funds through the legal acquiring of their personhood through matrimony.

- The way Shylock also attributes the word breast to Antonio when describing from where on Antonio he would like to extract the pound of flesh subtly feminizes Antonio, as breast during this time period maintained a neutral status but with implied reference to the female sex. The notion that an indebted Antonio would be feminized in contrast to a wealthy Shylock who maintains his masculine status subtextually implies further links between wealth as a symbol of power, and therefore a characteristic of the male sex.

- Portia’s reference to the balances or scales does not only serve a functional purpose in the play (she seeks to physically weigh the flesh Shylock cuts from Antonio) but subtly alludes to an ancient tradition in which material scales are used to weigh the immaterial, such as a life or a soul. This tradition dates back to the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, where in the Book of the Dead, hearts are infamously weighed against a feather under the watchful eye of the god Anubis and the goddess Ma’at, a goddess worshipped for maintaining order, and extended into Ancient Greece, where scales were attributed to the goddesses Dike and Themis to represent their combined responsibility to enforce divine law, justice and moral order. The weighing of morality via a balanced set of scales by the Ancient Egyptians and the Ancient Greeks quickly carried over in Medieval Europe, where the “weighing of souls” became the most heavily utilized motif in medieval Christianity. Thus, this is a particularly critical allusion as Portia’s request for the scales inherently situates her in an elevated position akin to previous pagan goddesses charged with maintaining justice and order, Ma’at, Dike and Themis. Shylock may possess the scales, but it is Portia who will read them and this subtle association of Portia successfully reading an object that represents both feminine divinity (by calling on a tradition of goddess who utilized the same object) and moral authority (the scales were used to judge someone’s heart, life or soul) implies to the reader that she inherently holds a higher status than Shylock in this exchange, and orients the reader to perceive her as a genuine source of authority despite her gender.

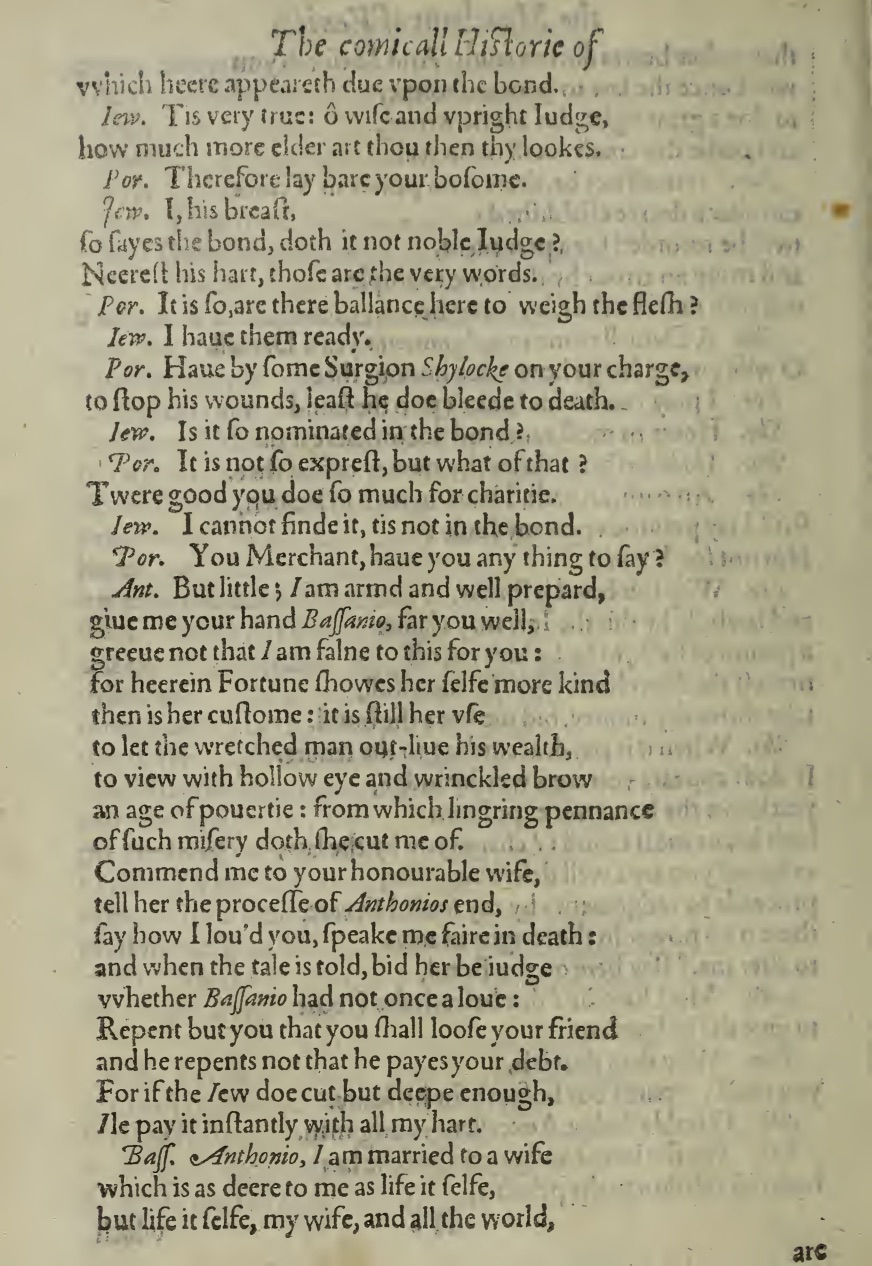

- The speaking tags as seen in this edition recognize Portia as Portia, despite her costumed appearance as a male judge. The decision to refer to her character name as opposed to her assumed character in the scene demonstrates that, regardless of the intention, a line has been typographically drawn between fiction and reality; in the scene, through dialogue, Portia is referred to as the judge, but outside of that “internal” text, in the margins where speaking tags lie, the reader is alerted to Portia’s “real” or “true” identity as a woman while she exercises her power in the courtroom. This decision opens interpretation regarding the gendered power dynamics of the scene, and invites the critical thought that understanding Portia’s gender in this scene is important to fully grasping it’s meaning.